Almost every adult in America knows that Teddy Roosevelt, with the wise counsel of Pinchot, had built a substantial part of his legacy on the protection of the nation’s natural resources. The Weeks Act was sponsored by New Hampshire born and raised, Congressman John Weeks, now a Congressman from Massachusetts. Weeks had moved to Massachusetts for work but maintained a Summer residence in the area of the family homestead. Today the Weeks Estate is a part of the New Hampshire State Park system and part of the estate in listed in the register of national historic sites. In the act, Weeks had stipulated that “the federal government has the constitutional right amounting to a national duty to acquire lands for forest purposes in the interest of a future timber supply, watershed protection, navigation, power, and the general welfare of the people.”

Though recent interpretations of the Commerce Clause of the Constitution have confirmed the correctness of Week’s position, in 1910 there was little national experience with national investments to protect public resources and Weeks was running afoul of Senators and Representatives who were determined to keep the Federal Government from encroaching on the rights of their states to control these lands, especially because many of these same Senators were beholden to the timber interests in their own states. Until a Supreme Court Decision could clear the way on this matter, it was incumbent upon Weeks, Roosevelt, and conservation leaders from throughout the country to secure specific permission from the Congress to make land purchases that protected watersheds and the people and environments they served.

A substantial number of the votes needed to pass the Weeks Act would be required to come from Southern Congressmen and Senators. Roosevelt and Pinchot were appealing to the enlightened self interest of these representatives by calling upon their constituents to use their political clout. Although the Week’s Act did not contain provisions covering the forests and lands of the South, it would not be long before they too would see its benefits for they too had experienced similar problems. By the time conservationists had gathered together for this conference more than 50% of the South’s original woodlands were gone and a sense of alarm about the sustainability of the forests was beginning to grow. This concern put them four-square in alliance with the conservationists of the Northeast who were raising the alarm over the devastation of the woodlands in the Northeast.

|

| Learning to Fish |

TR and Gifford Pinchot left the conference that fateful day with the explicit support of this powerful southern conservation organization for the Weeks Act and, in a little recognized historic moment, may have made the difference for the struggling Weeks Act because these conservationists launched a ripple that soon would turn to a wave of reform. At their urging, states began passing laws that granted the US Forest Service and other Federal Agencies permission to purchase lands for the protection of critical watersheds and advocates could feel the winds beginning to shift.

|

| The Eye of the Stone |

The country itself was in the middle of a “great awakening”, today known as the Progressive Era. A time when science, and the newly emerging fields of social science, were on the ascendency and where research and progressive activism were becoming the twin driving forces of social change. The research gave legitimacy and power to ideas; and progressive activism lent direction and momentum.

Still there were those who resisted . . . the climate change deniers of their day. Speaker of the House Joseph Cannon responded to calls for the protection of critical lands with the simplistic quip that there “would not be one cent for Scenery;” proving that the simplistic soundbite is not unique to modern times.

According to many historians, Cannon was one of the most powerful speakers in American history. With Cannon at the helm, the House of Representatives rejected more than 40 different bills that would seek to authorize the purchase of land by the federal government during his eight year tenure. Fortunately for the Weeks Act supporters Cannon’s tenure ended in 1911 and in the final months of his speakership Weeks and NH Senator Jacob Gallinger, who had submitted an identical bill in the US Senate, were finally able to convince Cannon to at least remain neutral on the Act. With the support of powerful environmental conservation organizations like the Society for the Protection of New Hampshire Forests, which had already been advocating for the protection of critical watersheds for more than ten years, the Congress finally began to turn around. In early spring, March of 1911, President Taft signed the Weeks Act into law. Now the difficult task of establishing National Forests in the Northeast could begin.

|

| Daylight Fades on Eisenhower |

The first priority lands identified for protection were those around the Presidential Mountain Range in New Hampshire and the surrounding mountain ranges. These included the Carter Moriah Range - which extends into Maine - as well as the Franconia Range and the Pemigewasset River Wilderness area, where logging by steam engine had already laid most of the timbered land bare. The Forest Service and Conservation groups issued calls for donations of land and offers to sell at reduced rates.

Not surprisingly, logging consortiums that had already laid waste to many areas were more than happy to sell off land that would take nearly one hundred years to regrow its cash crop. For them this was an unexpected windfall (so to speak) and they were among the first to sign on. Still, a surprising number of public spirited citizens also stepped forward to join in the effort offering their property in these areas at substantial discount from market based prices with some even donating land outright. By 1915 a substantial portion of the lands that would become the White Mountain National Forest had been purchased or donated and on May 16, 1918 President Woodrow Wilson signed Executive Order 1449 creating the White Mountain National Forest in Maine and New Hampshire.

For those interested in the broader history of the White Mountains, a Centennial within a BiCentennial occurs on this auspicious occasion. In the year that the WMNF was first established Abel Crawford and his son Ethan Allen Crawford, had they still been living, would have celebrated the first one hundred years of the trail that they built to guide the first intrepid (European*) hikers up Mount Washington. The Crawford Path, the nation’s oldest continuously used hiking trail extended from the site of the Crawford’s original homestead and Inn, in Hart’s Location, to the summit of Mount Washington.

|

| Spring's Dance of Form |

The Crawford Path was initially built as a hiking trail but in 1698 Abel Crawford - at the ripe old age of 80 - accompanied by Ethan Allen, summited Mount Washington on horseback as the hiking trail was opened as a double duty “Bridal Path” to the summit as well.

Initially in the range of about 435,000 acres, today the WMNF has expanded to nearly 800,000 acres having most recently added woodlands in the Great North Woods section of New Hampshire. The forest plays a major role in what has become a nine (9) billion dollar a year outdoor recreation industry in New Hampshire, supporting nearly 80,000 jobs.

Interesting Links:

The Battle for the Weeks Act: http://bit.ly/WeeksActBattle

Record of the Vote on the Weeks Act: http://bit.ly/WeeksVote

The John Weeks Story: http://bit.ly/JohnWeeks

The Weeks Estate, Weeks State Park: http://www.nhstateparks.org/visit/state-parks/weeks-state-park.aspx

*While it is commonly believed that Native American people - mostly those of the Algonquin Speaking First Nations people - did not climb mountains, there is no solid evidence that this is anything more than an assumption on the part of early European settlers. The extent of the evidence seems to be based upon superstitions related by some early traders, both Native and European - to early settlers in the area specifically about Mt. Washington (“Agiochook” or “Agiocochook” in Abenaki an Algonquian speaking tribe and part of the Wabanaki Confederacy of tribes). These general superstitions may or may not have been true. Furthermore, general superstitions shared among members of the Algonquin people would not necessarily preclude an ascent by an individual First Nations hunter or traveler from either the Algonquin speaking tribes of the Wabanaki Confederacy or members of the Iroquois Confederacy who dominated the region of New Hampshire above Dixville Notch including the disputed territory known for a short time as The Indian Stream Republic. Hence, Darby Field, the white man credited with the first ascent of Mount Washington, may or may not have been the first person to the summit. We will never know for sure. We do, however, know that Field ascended Washington with two Native American Guides who went all the way to the summit with him. The names of those guides appear to have been lost to history. However, the fact that they summited the mountain with Darby Field is, in and of itself, reason enough to suspect the presumption.

About Wayne D. King: Wayne King is an author, artist, activist and recovering politician. A three term State Senator, 1994 Democratic nominee for Governor, former publisher of Heart of New Hampshire Magazine and CEO of MOP Environmental Solutions Inc., and now host of two new Podcasts - The Radical Centrist (www.theradicalcentrist.us) and NH Secrets, Legends and Lore (www.nhsecrets.blogspot.com). His art is exhibited nationally in galleries and he has published three books of his images and a novel "Sacred Trust" a vicarious, high voltage adventure to stop a private powerline all available on Amazon.com. He lives in Rumney at the base of Rattlesnake Ridge. His website is: http://bit.ly/WayneDKing . You can help spread the word by following and supporting him at www.Patreon.com/TheRadicalCentrist .

|

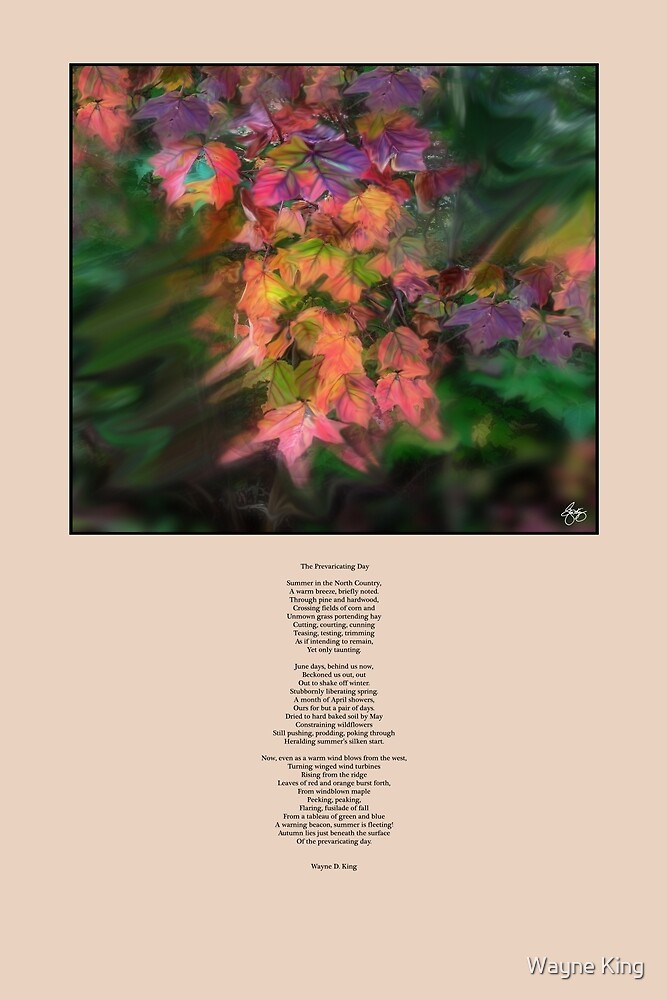

| The Prevaricating Day Purchase a signed original here. |

No comments:

Post a Comment